Building on work that first began in Massachusetts as part of the Vision Project, nine states have reported success in developing a shared, statistically valid assessment model that can be used to highlight and compare what college students actually learn.

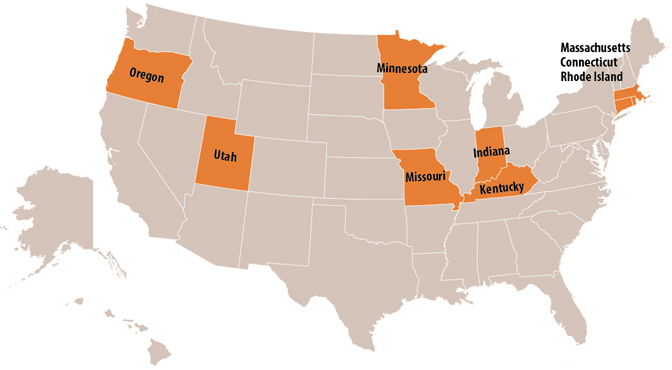

In 2015, the Multi-State Collaborative to Advance Learning Outcomes Assessment (MSC) invited faculty from 59 two-year and four-year institutions in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Indiana, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Utah to score more than 7,000 samples of authentic student work. They used a new web-based platform that allowed them to upload and assess each assignment using the Association of American Colleges and Universities’ VALUE (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education) rubrics to measure quantitative reasoning, critical thinking, and written communications. The goal of the pilot was to see whether the VALUE rubrics could provide an adequate measure of student learning across institutions and state lines.

Getting faculty to participate in such an assessment project was considered a breakthrough of sorts, given longstanding resistance to standardized testing at the post-secondary level. Without a new assessment model, proponents argued, campuses might eventually face state-imposed, high-stakes exit exams, a by-product of rising concern about the value of higher education.

The Chronicle of Higher Education reported that, across the nine states, scores for critical thinking were lower than those for quantitative reasoning and written communication. Scores for written communication and quantitative reasoning showed students struggling with use of sources and evidence, and having difficulty analyzing data. The results of the pilot gave faculty detailed feedback that could be used to reshape both instruction and assignments.

Christopher K. Cratsley, director of assessment at Fitchburg State University, told The Chronicle that FSU’s own assessment efforts utilizing the VALUE rubrics revealed opportunities to improve assignments designed to assess quantitative reasoning. “We’ve seen that some assignments are sometimes not as good at soliciting these skills as other assignments,” he observed. “That helps us think about how we create a balance in the instruction we give.”

Massachusetts’ work to create a systematic approach to the assessment of student learning stands in contrast to past experience of other states, where high-stakes exit exams have been imposed by legislatures or governors anxious to quantify the “return” on investments in higher education.

Through the Vision Project and the Multi-State Collaborative it spawned, faculty across all three segments of the Massachusetts system—and nationally, across nine states—have been full participants in efforts to create a new approach to assessment, one that would not only track outcomes to measure ROI but also provide detailed feedback to improve instruction.

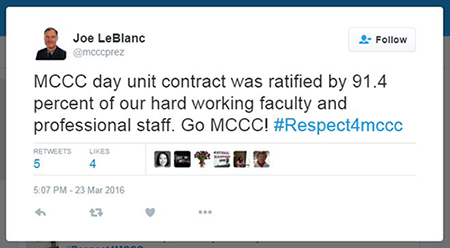

In recognition of faculty’s signature role in assessment, the Massachusetts Community College Council (MCCC) recently agreed to new contract provisions that, for the first time, recognize the importance of assessment while acknowledging both the inherent risks and additional responsibilities it will require of faculty. The contract, overwhelmingly ratified in March 2016, stipulates that faculty must include a list of student learning outcomes as a part of the syllabus for every course they teach. It also makes clear that they will not be evaluated on the basis of students’ learning outcomes and affirms that “the development, implementation, and assessment of Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs) require the systematic involvement of faculty and appropriate unit professional staff.”

“Our Massachusetts community college faculty have been national leaders in developing tools to assess student learning in the classroom,” said Lane Glenn, president of Northern Essex Community College and a participant in the negotiations. “We’ve found that learning outcomes assessment tools lead to improved teaching and learning and also are a very effective way to demonstrate college accountability to accrediting agencies, legislators and the public. Every college will help support faculty in this essential work.”